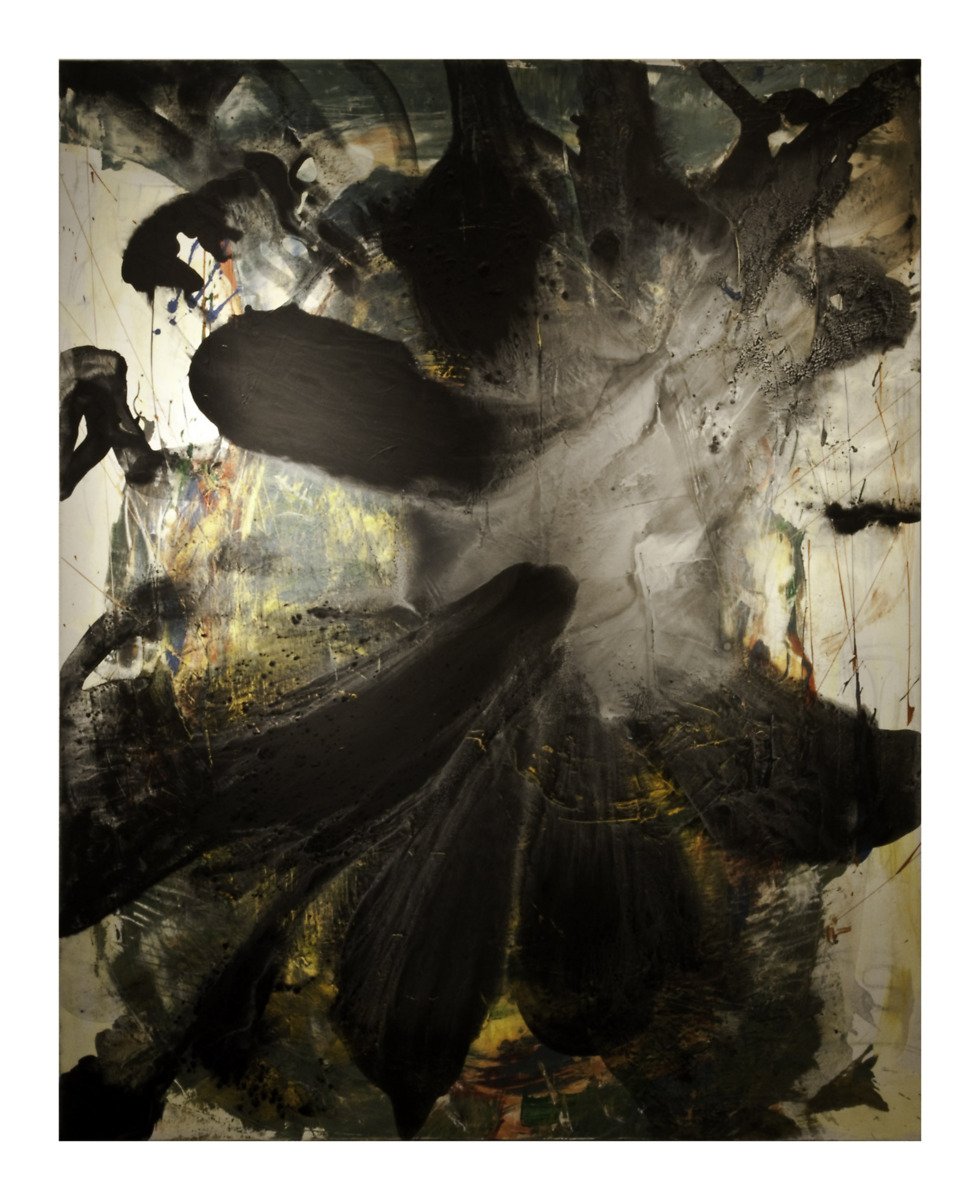

A Cycle, 2009

Ceramic, found object, steel, acrylic on canvas, and wood.

Art Foundry Gallery, Sacramento, California, USA

A CYCLE: ART FOUNDRY GALLERY By Square Cylinder Magazine

If Alan Chin looks a bit weary, there’s a good reason. In the past 48 hours he’s slept for about three hours, which, as it turns out, is pretty typical for the 22-year-old artist, who when I met him at Sacramento’s Art Foundry Gallery, had just finished a 6-month sprint: making the 50 plus objects that he and a crew of eight friends had finishing installing several nights before, at 3 a.m.

Chin’s output, which includes several distinct styles of abstract painting and sculpture (in clay, wood and steel), feels like the work of at least three artists – and, quite possibly, evidence of a bionic level of energy chained to a restless spirit. At 16 he was the youngest artist ever to be commissioned for the “Hearts of San Francisco” a benefit project for the San Francisco General Hospital Foundation. That was in 2003. Since then he’s shown in France, Italy and the Netherlands and in the Bay Area. He’ll complete his BFA degree at California College of the Arts (CCA) next year.

His strongest canvases have a haunted, spectral quality that recalls Helen Frankenthaler’s "pour" paintings; while his large-scale ceramic sculptures, reminiscent of Miro’s, feel totemic and iconic, like relics of a lost civilization. Chin speaks effusively about these influences, while praising the CCA instructors who have mentored him, particularly Raymond Saunders (for whom he works as an assistant) and the ceramic sculptor John Toki. But his biggest influences seem to have come from outside the classroom.

The son of two highly successful graphic designers, Chin grew up surrounded by affluence, fine art and plenty of art-making materials, and he credits his parents, who once gave Thiebaud prints to friends as gifts, with helping him develop a keen self-critical sense, particularly in regard to aesthetic choices. “They would tell me, ‘This is a sophisticated color. This is a subtle color. This is a hot color. This is too vibrant to use. From his grandmother he learned about ancient rituals practiced by monks in northern China which figure prominently in his ceramic sculpture, much as the visual tropes of Louise Bourgeois do in his steel works.

When he was five years old, he watched his home burn to the ground in the Oakland hills fire of 1991, and during the past five years, 24 of his friends and relatives died. “It was a sense of death and loss when I was a child,” an inkling of “wow, this can happen,” he recalls. No surprise, then, that mortality looms large in his art. Chin’s two Bourgeois homages feature spider-shaped, steel armatures under which ceramic figures cower. “I’m trying to convey the emptiness you feel when you know your body’s there, but you feel worthless and empty and totally ripped out and wonder: ‘How am I alive? How am I still functioning?’” Chin tries to find out by examining the very essence of life in his paintings. He made them from photographs of window glass taken with a fluorescent microscope which illuminated the cell structure of water that had crystallized on the surface. He manipulated the pictures on his computer and rendered the results more or less realistically, yielding loose, biomorphic images that look like mash-ups of oil stains and Rorschach blots. In a similar fashion, his large ceramic sculptures refer directly to trees that burnt on his family’s property. They’re glazed with the same metal alloy of car wheels that melted in the blaze. Chin can also be topical. His “Surveillance” series of ceramic sculptures, which have orifices or eyes, came out of his experience in London, where every street is watched by omnipresent CCTV cameras. He found Britain’s so-called “surveillance society” unnerving.